The Lasting Legacy of George Washington

We all look up. We look up to the Heavens with our hearts to see our Creator. We look up to the stars with our eyes to see the infinite universe. All things good, grand, and noble exist in an intangible place that only a direction called up can point our eyes and hearts to. Up is the path that perfection travels. Those of us flawed humans that come closest to that concept of perfection, we hold high and look up to them and call them heroes. Heroes are those who conquer fear to show courage. Heroes are those who overcome insurmountable odds to accomplish remarkable things. Heroes are those who show the rest of us, by example, the nobility of a flawed but humble human.

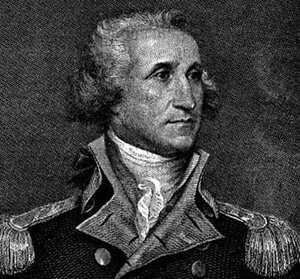

Despite the imperfection that afflicts us all, George Washington certainly lived a heroic life. The symbol of our nation’s founding, George Washington continues to set an example for humanity that inspires not only his nation but the world. Today, when our “heroes” are super, wear androgenous spandex armor and wield power beyond the ability of any of us mortals, it is inspiring to think and reflect on a true human hero like our first President. George Washington quietly showed us how to overcome our flaws and humbly rise to a higher place.

Born in Virginia on February 11, 1731, according to the Julian calendar in use at the time. When the British empire adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1752, Wednesday the 2nd of September was followed by Thursday the 14th of September. Those 11 days were subtracted to account for the adjustment, and because of the calendar change and the mathematics behind it, those born between January and April had to subtract a year as well as the 11 days. When he was 21 years old, George Washington’s birthday changed from February 11, 1731, to February 22, 1732. The date we recognize as his birthday, if not the day we celebrate it.

The calendar change was part of a new world paradigm. The age of enlightenment was in full swing throughout Europe. George Washington lived at a pivotal moment in human as well as our nation’s history. As the world began to embrace a more enlightened view of the natural world, Washington was not only a witness to grand changes in human history, but he also helped shape that history with his leadership and by the example he left for the generations of Americans that would follow.

In 1754, an inexperienced 22-year-old farmer from colonial Virginia, Major George Washington, leading a provisional force of British soldiers and Virginia militia met a stinging defeat at the hands of a much larger French and Indian force at the Battle of Fort Necessity while attempting to protect British interest in the Ohio valley. This military failure shaped Washington’s perception of the battlefield and taught him the value of training and supplies and the importance of inspirational leadership.

Despite the insight gained on the battlefield, because of poorly translated terms of surrender signed after the battle, Major Washington unknowingly took responsibility for the assassination of a French diplomat who was killed in a skirmish. This set into motion a series of events that led to a global conflict called the Seven Years’ War. Sometimes called the “first world war,” this conflict turned North America into a battlefield that restructured the European political order and would prepare a young nation and her future leaders for a war for independence.

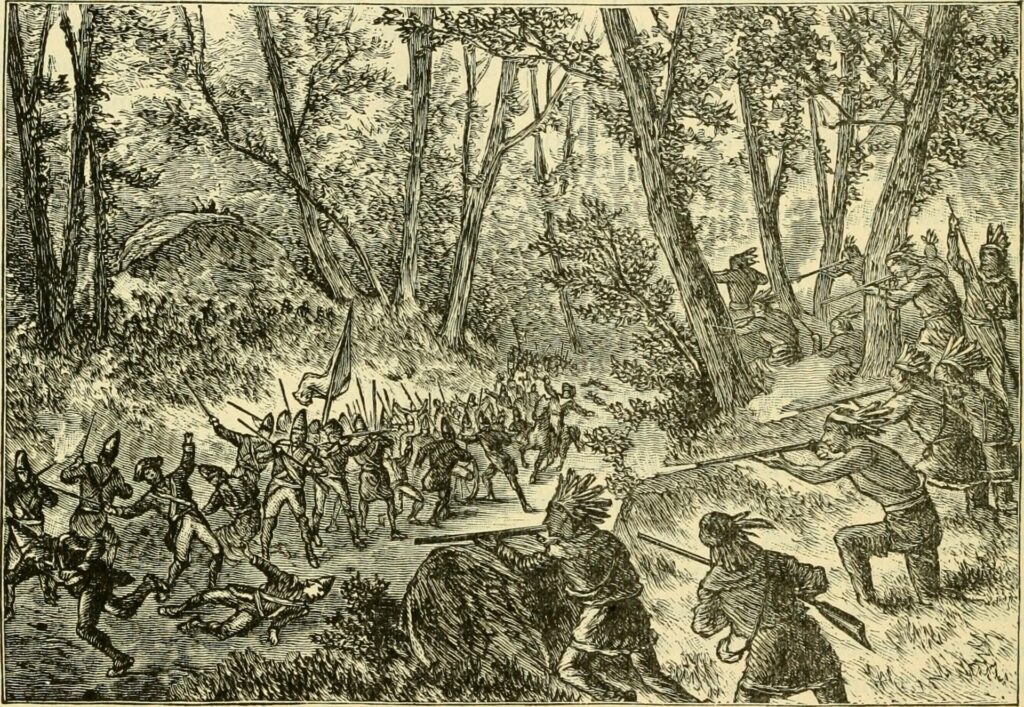

It was in 1755 during the French and Indian War that George Washington showed his prowess as a strategic thinker and revealed the calm demeanor of a fearless and capable leader under fire. Promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in the Virginia Regiment, Washington was serving as aide-de-camp to General Braddock, the commander in chief of the British Army in America. General Braddock led a military expedition to capture the French Fort Duquesne in the Ohio Country. At the Battle of the Monongahela, the lead elements of the British army ran into the French and Indian forces who were on their way to set up an ambush for the British. Braddock ignored Colonel Washington’s warnings about operational flaws in their battle plan. Braddock’s “gentleman” warfighting methodology led to 456 fatalities and 422 wounded for the British, including General Braddock who was shot off his horse and killed after hours of intense combat. Officers were prime targets for the French and Indian sharpshooters, leaving 26 officers killed and 37 wounded.

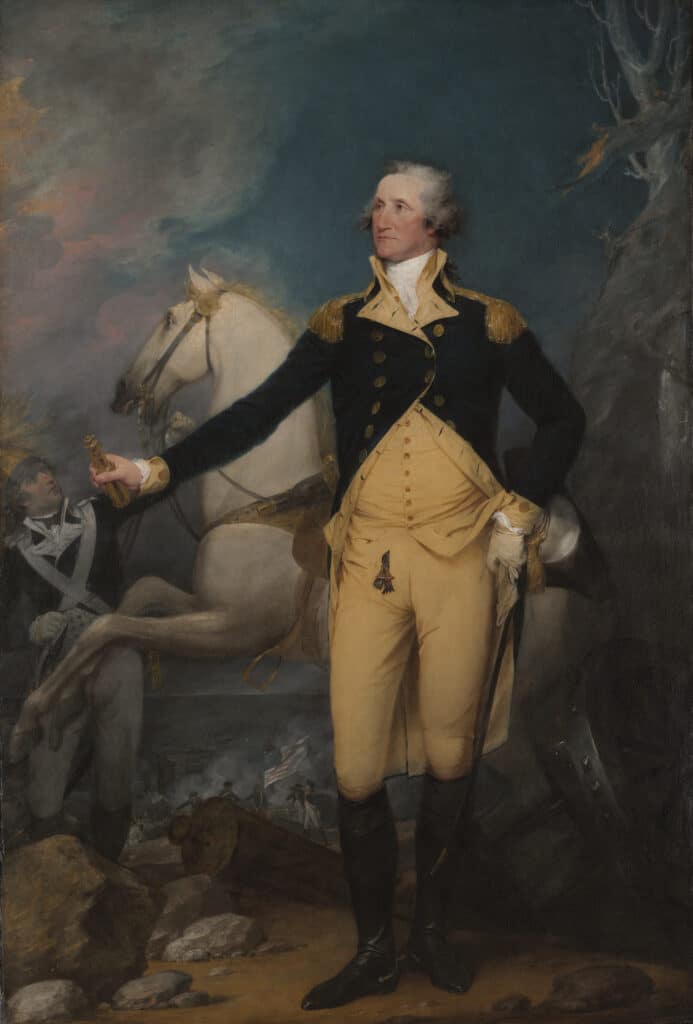

With no effective leadership, the British lines were collapsing when Colonel Washington, who had no command role, rode forward, and rallied the troops into an effective rear guard. Washington’s actions allowed the remnants of the British forces to disengage and withdraw. While doing this, he had two horses shot out from under him, and his coat had no fewer than 4 holes from musket balls fired at him by sharpshooters. His courage and leadership earned him the sobriquet Hero of the Monongahela which established his reputation as a military leader.

In 1758, after having served in the Colonial Militia, fighting for Britain in the French and Indian War and subsequent Seven Years War, and seeing no future in the British army, Washington resigned his commission and eagerly returned to his family farm, Mount Vernon in Virginia to resume his life as a gentleman planter. He married Martha Dandridge Custis in 1759 and assumed management of the 25,500 acres of farm and estate land he and his wife owned. Washington was an industrious early riser who worked the land 6 days a week, leaving Sunday for worship, entertaining friendships, and maintaining correspondence.

Fundamental to Washington’s success as a gentleman farmer was self-sufficiency and willingness to innovate and experiment. “In many ways he was a scientist. He performed many experiments with plants to enhance his plantation. He had a greenhouse. He designed a barn where horses would trot over wheat to separate the grain. Mount Vernon has recreated it. The horses trotted over grating so the gain would fall to a level below.” says George Washington historian, John Koopman III, author of George Washington at War – 1776. Koopman adds, “Washington was a man of faith and of science. He believed that he lived in an enlightened age.”

Ten years later, a wealthy landowner, a devoted husband and committed father to his wife’s two children, George Washington had a lot to lose by opposing British rule. In a letter to George Mason in 1769, Washington said, “At a time when our lordly Masters in Great Britain will be satisfied with nothing less than the deprivation of American freedom, it seems highly necessary that something shou’d be done to avert the stroke and maintain the liberty which we have derived from our Ancestors,” but armed resistance “should be the last resource.”

In 1774, after several attempts by the colonies to change the antagonistic approach of the British, Washington became more aggressive in his rhetoric, declaring he would “raise one thousand men…march myself at their head for the relief of Boston.” Later that year, he was selected to represent Virginia in the 1st Continental Congress where he famously wore his full military uniform.

On April 19, 1775, after musket fire was exchanged between colonists and British troops, the Revolutionary War had begun. Two months later, on June 14, 1775, the 2nd Continental Congress resolved that the Continental Army be established with 6 companies of expert riflemen. Five days later, the Continental Congress commissioned George Washington as Commander in Chief of the Continental Army. Like the Roman hero Cincinnatus, the farmer became a soldier, this time in service to his country.

Defeating the world’s most powerful army was seen as an impossible task for Washington and his untrained, inexperienced Continental Army. Against all odds, General Washington balanced boldness with caution, seeking decisive battles and revealed an indomitable will to persevere to protect and defend the nation. Victory was anything but certain.

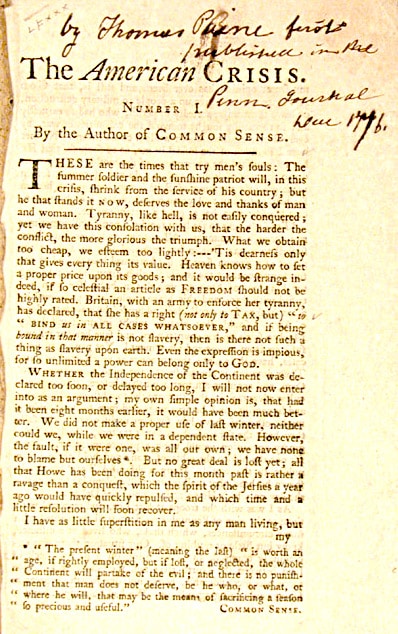

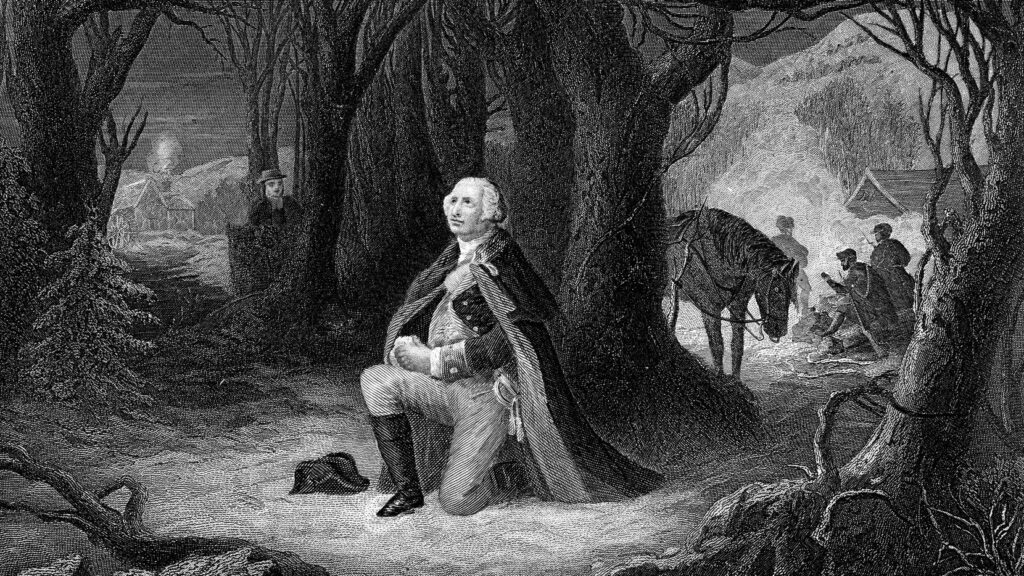

As winter of 1776 set in, recent military defeats in New York and New Jersey left the Continental Army on the verge of collapse along with the entire patriot cause. The losses left the army suffering from poor morale. Enlistments were ending, and the inclination to leave the army was greater than to stay.

The publication of The American Crisis by Thomas Paine reinvigorated the morale of the patriot cause by extolling the virtues of those who stayed to fight and “that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.” General Washington ordered it to be read to all his troops, encouraging them to stay in the fight.

Seeking a bold move against the Hessian forces that had bedded down for the winter in Trenton, New Jersey, General Washington led a daring sneak attack across the icy Delaware river. In the early morning of December 26th, he caught the Hessians by complete surprise and was able to secure victory with only three Americans killed and six wounded. The Hessian commander, along with 22 of his soldiers were killed. The Americans captured over 1000 Hessian prisoners and valuable military stores of ammunition and weapons.

After quickly returning to Pennsylvania across the Delaware river with his army and prisoners, General Washington learned that the British forces were still in disarray in New Jersey. Recognizing the opportunity, General Washington crossed the Delaware river a third time on December 30, 1776.

At the Battle of Assunpink Creek on January 2, 1777, General Washington punished the British General Cornwallis’ forces with withering fire that led to heavy losses for the attacking British troops. Multiple attacks were repulsed by the Continental Army, forcing Cornwallis to consolidate his forces for another attack with reinforcements the next day. When the sun rose, the light of day revealed to Cornwallis that the “old fox” General Washington was gone, the empty American camp evidence of their rapid departure in the evening before. Washington had maneuvered his forces north during the night for an attack on the British garrison in Princeton.

During the Battle of Princeton, on January 3, 1777, General Washington showed his battlefield acumen when his Continental Army troops were close to being routed. After being overrun by the British garrison troops, Continental Army forces fell into retreat when their commander General Mercer was mortally wounded. Militia forces sent by Washington to help the army saw the fleeing troops and joined them in their flight. General Washington rode into battle with reinforcements and rallied the fleeing militia, shouting, “Parade with us my brave fellows! There is but a handful of the enemy and we shall have them directly!” With his hat in hand, General Washington rode forward of his troops and waved them forward, ordering no one to fire until he gave the signal. When the British troops were thirty yards from him, he wheeled his horse, faced his men, and ordered them to halt, and then gave the command to fire at the British behind him. At the same moment, the British troops opened fire, covering the field with an obscuring cloud of smoke. One of Washington’s officers covered his eyes with his hat to avoid seeing General Washington killed, but when the smoke had cleared, General Washington was still on his horse, unharmed and waving his troops forward to victory, driving the British from the field.

With three decisive victories over the British in less than 10 days the spirit of the patriot cause in the nation was rejuvenated, bringing a belief that they could win the war. The victories of Washington and the Continental Army at the Battles of Trenton and Princeton forced a retreat of the British out of Central Jersey and bolstered the morale of the army, encouraged recruitment, and impressed the French King, Louis XVI, who was actively contemplating France’s involvement in the war with their old rival.

At the time, the British treated the battles at Trenton and Princeton as if they were minor skirmishes and their loss was of no import. Although the British historian Sir George Otto Trevelyan wrote of the victories at Trenton and Princeton, “It may be doubted whether so small a number of men ever employed so short a space of time with greater and more lasting effects upon the history of the world.”

By 1781, after six years of fighting, both sides are near exhaustion. The British are also involved in another global conflict with both France and Spain that is taxing their ability to wage what is otherwise seen as an unpopular war against the American colonies. In the summer of 1781, General Washington and his French allies sense an opportunity to seize victory and decide to take decisive action again. Through deception, the American and French forces convince the British that New York is going to be the target of their siege. Instead, the combined forces of the Continental Army and the French Army march secretly and rapidly to the south, encircling General Cornwallis in Yorktown, Virgina. With a French Naval blockade of the Chesapeake, Washington is able to bombard the trapped British forces, compelling a hopelessly shamed General Cornwallis to surrender on October 18th.

The victory at Yorktown was decisive. There were no more land battles after the British surrender at Yorktown. Washington and the Continental Army had overcome insurmountable odds to defeat the most powerful military on Earth and defended their newborn nation’s right to exist. After the Treaty of Paris was signed in September of 1783, the War was officially over, and the United States of America had gained recognition of its existence as a free, sovereign, and independent states.

On December 23, 1783, at the statehouse in Annapolis, Maryland, General Washington surrendered his military commission granted by Congress and all the power that went with it. Before the gathered congressmen, Washington said, “Having now finished the work assigned me, I retire from the great theatre of action, and bidding an affectionate farewell to this august body, under whose orders I have so long acted, I here offer my commission, and take my leave of all the employments of public life.”

The news of George Washington voluntarily giving up his political power to return to his farm spread like a fire across the globe. Across the Atlantic Ocean, his former opponent, King George III told American artist, Benjamin West, “If Washington does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.” American painter John Trumbull in London declared that Washington’s voluntary resignation “excites the astonishment and admiration of this part of the world. ‘Tis a Conduct so novel, so inconceivable to People, who, far from giving up powers they possess, are willing to convulse the Empire to acquire more.” The Maryland delegate James McHenry remarked, “the events of the revolution just accomplished—the new situation into which it had thrown the world—the great man who had borne so conspicuous a figure in it, in the act of relinquishing all public employments to return to private life. . . all conspired to render it a spectacle inexpressibly solemn and affecting.”

Washington’s reluctance to hold power made him the ideal person to give power to. Despite his desire to return to Mount Vernon and live the life of a farmer, Washington’s retirement was short. At the first Constitutional Convention in 1787, he was elected as its president. After ratifying the Constitution, Washington was unanimously elected to be the First President of the United States. After serving two terms, establishing a trend that was followed until the 20th century, Washington retired on March 4, 1797, voluntarily giving up power one last time.

Washington finally returned to Mount Vernon to spend his final years on his farm. Before he died, he addressed an “unavoidable subject of regret,” the presence of slavery, not only on his own farm, but in his newborn nation of free people. Washington’s position on slavery is a complicated one. Born into a world that institutionalized slavery, his views changed over his life. The most profound changes occurred during the Revolutionary War, when he risked everything he had to fight for a nation that was predicated on the idea that all men are created equal.

Repeatedly, Washington told supporters of abolition his belief that the best way to eradicate slavery was through the legislative process and a gradual emancipation of the enslaved and added that he would gladly support any such measure introduced.

In 1786, Washington wrote to his friend, Robert Morris, about his fear that his opposition to methods of abolition would be interpreted as opposition to abolition itself: “I hope it will not be conceived from these observations, that it is my wish to hold the unhappy people, who are the subject of this letter, in slavery. I can only say that there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it; but there is only one proper and effectual mode by which it can be accomplished, and that is by Legislative authority; and this, as far as my suffrage will go, shall never be wanting.”

Nearing the end of his life, Washington lamented, “The unfortunate condition of the persons, whose labour in part I employed, has been the only unavoidable subject of regret. To make the Adults among them as easy & as comfortable in their circumstances as their actual state of ignorance & improvidence would admit; & to lay a foundation to prepare the rising generation for a destiny different from that in which they were born; afforded some satisfaction to my mind, & could not I hoped be displeasing to the justice of the Creator.”

After falling ill, George Washington died late in the evening on December 14, 1799. He was 67 years old. When he passed, he was surrounded by the people closest to him. His wife, Martha, his friends Dr. Craik and Tobias Lear, and his slave housemaids, Caroline, Molly, and Charlotte along with his slave valet, Christopher Sheels.

Two hundred and ninety-one years after his birth, our first national hero, George Washington, still sets an example we look up to. We see his bravery in the face of enormous danger, not for personal gain, but for the noble ideals of equality. We also see quiet humility in the face of unavoidable mistakes that stem from our flawed human nature, reminding us to always “labour to keep alive in your breast that little celestial fire called conscience.”

Howard Hochhalter

Director, Science and Nature Activities

The Hollow, Venice, Florida

Special thanks to John Koopman III, author of the book, George Washington at WAR – 1776.

Through conversations, emails and quotes, Mr. Koopman provided invaluable insight into the history and the mind of George Washington.